My name is Rodrigo Souza, but I’m better known as Rodrigo Maré, a reflection of the relationship I have with Maré itself. I’ve lived here 26 years, since my birth, and part of my family has lived here for more than 30 years, in Parque Maré and in Nova Holanda. At times people talk about this place as if it were just one favela – “such and such happened in Maré.” But Maré is huge, it has almost 20 favelas. Maré really is its own world, its own neighborhood, and like all neighborhoods it has its particularities, relationships, historical context, and so Parque Maré, Nova Holanda, each community is different.

I’m currently working with music and art. I began playing percussion through a social project here, working with constructing instruments with recycled materials, and out of that project we formed a band. After the project ended I studied at the State University of Rio de Janeiro in a project called Musikfabrik, which taught me a lot about the sound behind musical production. I formed a band there, and it was through it that I really matured and got to understand myself better as an artist and musician. We were a band of black musicians from the city’s periphery, and we worked with that resistance, of showing our faces and our musicality. From that point I began to study at a different music school, where I gained a theoretical and didactic side to give classes. It’s not just a matter of playing – behind that there’s a whole practice, a whole texture, there’s timbre, rhythm, parameter, and there I was able to learn that.

At that point my professor invited me to participate in a music school that works with researching and teaching popular culture. Within popular culture there are lots of rhythms brought from Africa, from batuque to samba, and it’s through teaching and studying there that I’ve learned to value this place. After Nigeria, Brazil has the most blacks in the world – what does that mean for this country? Sometimes we see Brazil as a country that’s lost within its mystique, within its culture. Brazilian musicality is black, and it needs to continue to be valued, restored, and deepened to continue existing. It’s important for our people to know where we came from in order to know where we’re going.

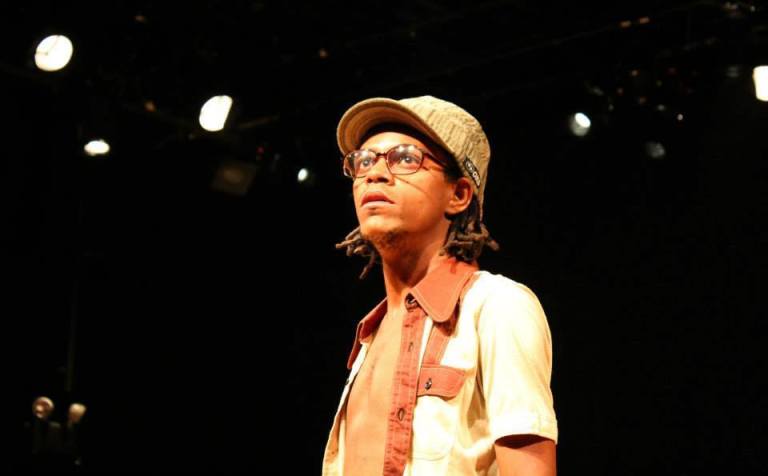

Along with what I do with music, it’s seven years now that I’ve been part of Cia Marginal de Teatro, a theatre company formed and founded by residents here of Maré. We’ve done four productions, the most recent one – “Eles nao usam tênis naique” (“They Don’t Wear Nike Sneakers”) – sold out nearly the entire time we performed. It was about a father who was a drug dealer during the 1970s and returns to find his daughter today within the same context in which he found himself, but in which the relations have changed. I did the score for the production; in all of the productions I play music too. With the reaction to our production, we’re seeing that the marginal is becoming more and more valued within the theatre of Rio de Janeiro.

Because like music, theater here is even more marginalized. We can talk about theatres, but where are they located? They’re in the zona sul, downtown. It’s not possible for a father or a mother with four kids to take the bus, pay 3.80 in bus fare for each child, to go see a play that’s going to charge 50 reais per ticket. A minimum wage is 800 reais per month – how are they supposed to survive within that context? Those who govern this city have to think about how they can foment that culture for people who are outside of its traditional context. They have projects that are marvellous, but they’re only for a certain public: the public that’s white, playboy, bourgeois, from the other side of the city, who don’t know how much we have to work to be able to consume that type of culture too. That’s the life that we have as marginalized people – we have to pray, to kill a lion every day to continue living in some way.

Before I was 18, 19 years old I had no experience playing music. I was doing other things – working, experimenting, figuring out who I was. I started and I liked it and I kept practicing to get to where I am today. That normal process we think of – learning from a young age – it’s a middle class process, for those who have the ability to put their kid in a theatre school at nine-years-old. When a boy of nine years says, “I want to be an actor, I want to be a musician,” it’s because he’s had contact with those things from that age. That’s why I say that we have to keep fighting so that these vehicles of culture are present here within the favela, so that a nine-year-old kid can be there every day doing theatre, going to a show.

We need to bring new perspectives, to bring hope, and it goes without saying that we need to be seen as citizens too. Because in public policies for security, the government spends millions of reais for tanks, helicopters, other weapons. Thinking about education, they’ve been constructing new schools, but the schools that exist are all crumbling. The teachers are crushed, their salaries are awful, the students have no perspective of improvement. There’s a number of cultural spaces that are also crumbling; here in Maré we have a cultural center but the workers haven’t been paid for three months. We need to emphasize these projects, these areas of artistic production as spaces of improvement for us, for the people of the favela, the people of the periphery, the people of the zona norte. We deserve to have vehicles, places of culture within our space.

And with all of this, I’m here. Every day I play music here, and as with everything within the favela, it becomes interpersonal – you make a sound, you start playing a drum inside and people will appear at your window. I’ll open my door and the kids will come in and we’ll have a class: I’ll talk a bit about music, we’ll make some noise. It’s important to bring that perspective so they see that here it’s not just guns, it’s not just drugs, it’s not just the police. There are also artists, there are also people who work, people who struggle daily, the truth is that they’re the majority of the people here. The media doesn’t want to say that the majority of people here are the workers who move this city forward, because that doesn’t sell newspapers – the more blood, the more deaths, the more newspapers they’re going to sell. That’s why I like to open my door for kids to enter, to produce music and sound, to speak to them about what’s behind it all and what’s possible here – that even with you being poor, even with you living in a favela, you can still be an artist, you can still consume art. It’s not just the privilege of the middle class and the bourgeoisie, it’s the right of every citizen.

My hope for the future is that black people – by which I mean the people from favelas, who are poor and black – see themselves in their full potential, and that we use that potential to empower ourselves, to stop accepting what’s imposed on us every day: racism, the death of our people with our city’s security policies, the idea that you can’t go to university, that you have to be a subaltern worker. Because we’re such a rich people, what’s missing is for us to see ourselves in that way. I think that when that happens everything’s going to change. It’s already changing, we’ve put ourselves in many new places, but it can be better. And I hope that we continue saying these things to our kids, and that they begin to see themselves as protagonists within their own history – as people who can do something, people who can achieve something, people who can lead.

Photos: Antonello Veneri/Henrique Gomes (Top); Marcus Galina (Bottom)

Rodrigo’s story is truly inspirational. I love what he said about empowerment and achievement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was wonderful! Thank you for sharing it, and for the important work you’re doing. I wish you much success!

LikeLike

Thanks Malka! Please keep reading : )

LikeLike